Bird Dog Trauma Kits

It happened fast. Most things do in the field. One moment, Ozzy was working the scrub oak on the hillside, trying to catch the scent of a Mearns’ covey another Pointer had already found. The next moment, the quail burst from a cluster of native grass and flushed two different directions. I dropped a single. My hunting partner fired two shots toward the group of birds heading up and over the hillside.

I retrieved my bird—my first Mearns’—and was thrilled, until my partner started shouting my name. I turned to look, and saw him kneeling with Ozzy by his side, a bright streak of red running down Ozzy’s front left leg.

Two lead shells of 16 gauge had hit my dog. He’d been half-hidden behind a scrub oak, and the quail had flushed straight toward him. The shrub helped dissipate the shot, but he still took twenty-plus pellets of lead to the face, body, and legs. Most of the wounds were superficial. But one pellet hit Ozzy’s superficial brachial artery, and he was bleeding out.

We were two miles from the truck. Two hours from the nearest vet. And I didn’t have a real trauma kit. I had the same kind of trash “first aid kit” I’d carried for years; the standard bird dog kit everyone sells and everyone buys. Great for nicks and cuts. Great for cleaning foxtails out of ears or flushing a junked-up eye. It was a kit built for inconvenience, not catastrophe.

Ozzy stood by my side, panting, seemingly oblivious to his wounds. There’d been no yelps or whimpers, just silence after the shots. I knew the severity the injury—I’d seen plenty in training and in Afghanistan—and I knew I had a few minutes, at best, to stop the bleed. As I clamped Ozzy’s leg with one hand, and rummaged through my first aid kit with the other, I had a sinking feeling I’d failed my dog. I tried to find a solution, and pushed away the intrusive thought circling my mind: that I’d spend the coming minutes watching Ozzy die slowly, a few hundred meters north of Mexico.

I improvised a tourniquet with a slip lead and stick. It wasn’t pretty, but it stopped the bleed long enough to get him off the mountain. It took us 90 minutes to link up with a vet on the roadside for a tailgate surgery. The bleeding had stopped, and a bag of fluids got Ozzy’s blood pressure trending in the right direction. We’d bought him enough time to get to an emergency vet and wait to see if he’d survive the night.

Ozzy lived. I wouldn’t call it luck—I’d call it a warning.

A few days later, I called an old teammate from my Special Forces days. He’d moved on to a Special Mission Unit as a canine handler. Those dogs go through hell, and the medics who keep them alive see things a normal hunter never will. My friend listened while I laid out what happened. He sent me one of his Canine Bleeder Kits and walked me through the logic behind every item. No fluff. No dead weight. No “hunting brand” filler. Just what works, and why.

That conversation changed how I hunt. Not the way I move through the terrain, but the way I prepare for the consequences of the terrain, the birds, and the mistakes. Run dogs long enough, and something bad will happen. It might be barbed wire or a fall. A rattlesnake bite or a wrong step off a scree slope. Or it might be someone’s shot string catching the edge of your dog as he quarters through the brush.

You don’t get to chose those catastrophic moments. You only choose whether you’re ready.

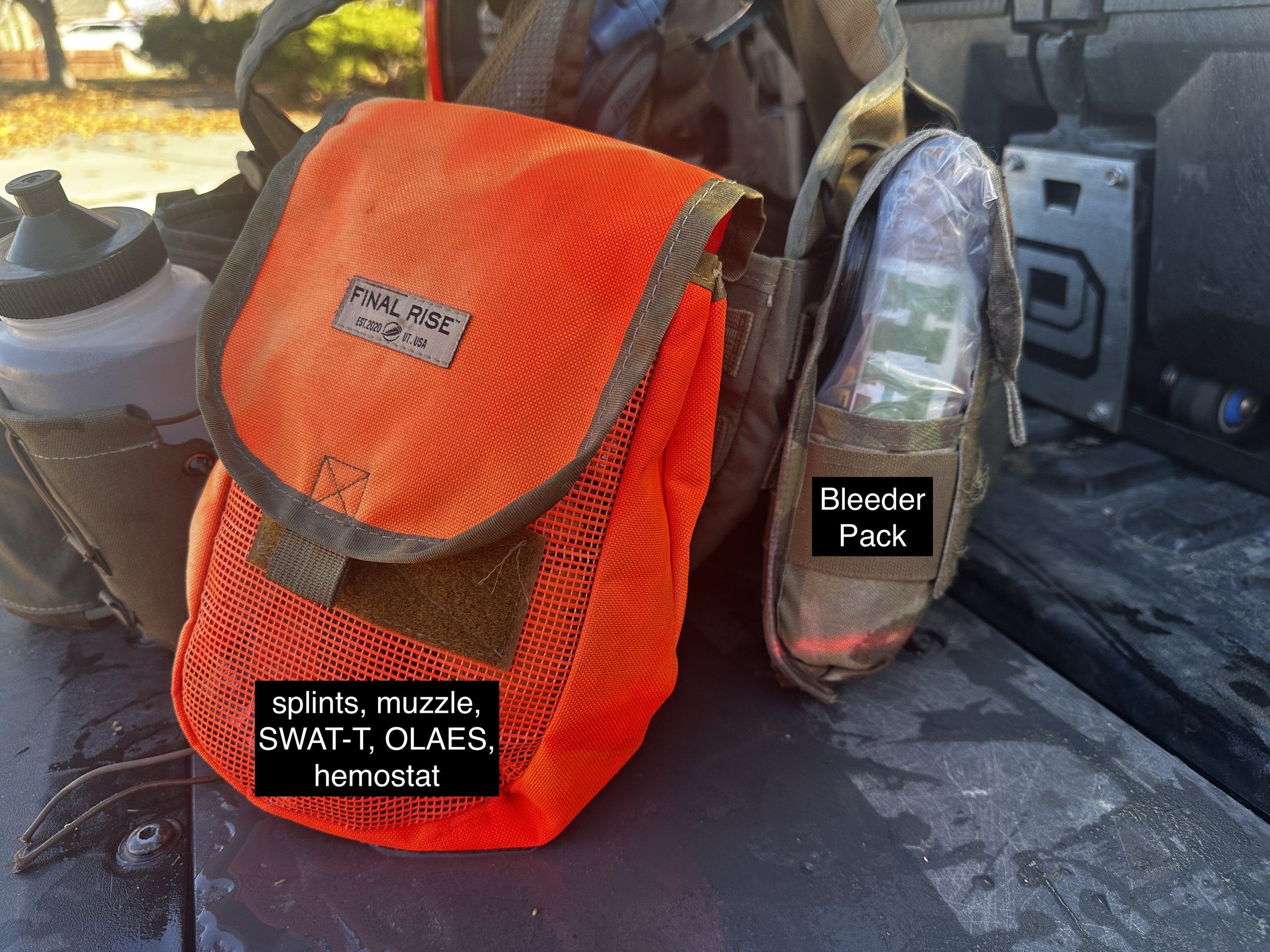

So this is the trauma kit I carry now. Not because I want to, but because I’ve knelt next to a bleeding dog and felt the bottom fall out of my chest. And because I’ve learned that “good enough” just isn’t.

There are five categories of gear. All prioritized, all necessary. You can tailor it to your terrain and style of hunting. But the order matters, and the reasoning matters. It’s not theory. It’s what keeps your bird dog alive long enough to get him to a vet.

1. Hemorrhage Control

If you can’t stop the bleeding, nothing else matters. This is the first category for a reason.

I carry two SWAT-T tourniquets now. They’re simple, durable, and, unlike some other tourniquets, they actually work on dogs. You can use them on limbs, or you can wrap and secure a dressing or splint. When Ozzy got shot, this alone could have saved him.

I keep compressed gauze for wound packing.

And QuickClot Combat Gauze for when regular packing isn’t enough.

I carry a curved hemostat for clamping an exposed artery. Hemostats are not something you want to use unless you need it, but when you need it, nothing else will do.

I’ve tried ChitoGauze too. It works, but it’s rigid and awkward on a dog. I’d rather have an extra QuickClot instead.

This is the category most people underpack. It’s the one you shouldn’t.

2. Airway & Respiration

Dogs can survive a lot. What they can’t survive is being unable to breathe.

I carry two HALO chest seals and petroleum gauze strips for sucking chest wounds, and a 14ga × 3.25" needle decompression kit.

The decompression kit requires training, because a poorly placed needle can kill a dog faster than a collapsed lung. Same for the cricothyroidotomy kit—it’s only useful if you know how to use it.

3. Evisceration

If a dog gets gutted—barbed wire, a branch, a bad fall—you need to cover and secure the intestines. If you can, spray some saline on them first to keep the innards moist. I use an OLAES modular bandage and will wrap it with a SWAT-T to keep everything secure.

4. Gastric Dilation–Volvulus (Bloat)

It’s not always gunfire or cliffs that take a dog. Sometimes it’s his own anatomy turning on him.

If you know, you know. If you don’t, read up.

The same needle used for decompression of the chest can be used to remove the gas buildup from a twisted stomach. I carry one, but two would be better.

5. Fractures

A fall, a rolling boulder, a bad landing—dogs are athletes who don’t always land like one.

I carry two 36-inch SAM splints.

Avoid the small, canine-specific ones. You can always cut down the splints, but you can’t make them longer. Plan on multiple attempts to get the splint correctly placed, and use the SWAT-T to secure it.

Additional Gear

These are everyday items that become essential when the day goes sideways:

- cohesive bandage

- trauma shears

- skin stapler

- saline

- ear wash

- Benadryl

- Gorilla tape

- rectal thermometer

- muzzle (muzzle the dog before treatment)

- dog boots

Out West, I also prepare for rattlesnakes, coyotes, mountain lions, barbed wire, scree, and heatstroke. Heat kills quickly. I keep a running log of my dogs’ resting and working temperatures in different atmospheric conditions. If you do that long enough, you can catch the temperature cliff before they fall off it.

If you hunt in trapping country, carry wire cutters for snares. For body gripping/conibear traps, the Minnesota Trappers Association Dog Release Kit is simple and light.

Carrying a Dog Out

Treating the dog is one thing. Getting him out is another.

I hunt solo most of the season. There’s no one to help carry my fifty or seventy-pound dogs down a ridge while trying to keep pressure on a bandage. I use a Final Rise vest because it’s built well enough to haul a dog on your back, but it’s not perfect.

Back-carrying makes it hard to monitor bleeding or breathing. A panicked or injured dog fights, and it’s hard to manage the animal, the injury, and the terrain by yourself.

RuffWear makes a front-carry harness that solves some of this, though it’s another piece of gear to haul around.

I’d rather reverse-wear the Final Rise vest, but have the bird bag modified to open on the sides so the material doesn’t dig into the dog’s ribs and armpits. If you hunt alone long enough, you start thinking about things like that.

A Second Chance

Ozzy recovered. You wouldn’t know he’d been shot unless you ran your fingers along his ears and ribs and felt the pellets hiding below the surface of his skin. He hunts as hard as he ever did, tail cracking back and forth like a metronome set to the rhythm of the hillside. Sometimes I watch him range out and think how close I came to losing him on that crisp morning in southern Arizona—how a few ounces of lead and the wrong contents of a first aid kit nearly took the dog I love.

Our bird dogs don’t get a choice. They go where we take them. They bleed when we make mistakes or when someone else does.

The least we can do is be ready.

Because when the moment comes, and someday it will, you won’t rise to the occasion.

You’ll fall to the level of your training. And to whatever’s inside your vest.

-dg sends